A Single Molecule View of Diffusion-Limited Bimolecular Association

The first step of biomolecular communication is the binding of two molecules, e.g., a transcription factor binding to the promoter sequence of the target gene or a drug binding to its target protein. Especially from the drug design point of view, it is useful to optimize the structure of the drug molecule such that this binding process is fast, specific, and robust.1 Moreover, the rate of such a binding process, also called the “on”-rate and denoted as \(k_{\text{on}}\), is commonly used to parameterize pathway models for cell signaling cascades.2 Such pathway models, in turn, act as cost-effective tools for in silico drug screening and target identification and prioritization.3

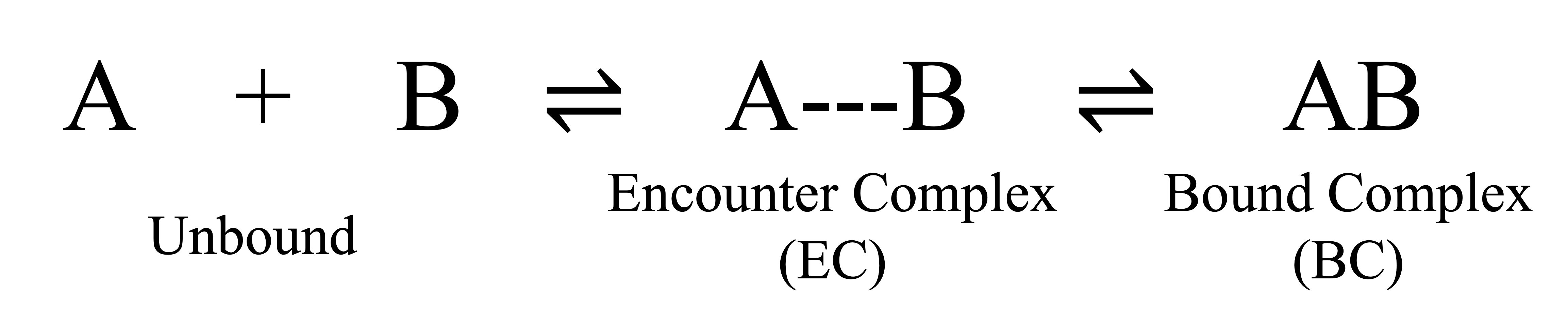

The Encounter Complex (EC)

A key concept within the theory of bimolecular association is the notion of the Encounter Complex (EC),4 5 or the set of structural configurations observed when the molecules first “encounter” one another, that may be characterized by non-specific interactions between the two molecules.6 7 Depending on the precise structure, orientation, and conditions of this encounter, the molecules may dissociate again or continue to form stable interactions, e.g., van der Waals, hydrophobic, or electrostatic interactions, with possible conformational rearrangements, and settle into a bound complex (BC).

Given an excess of computational resources, the exact on-rate (\(k_{\text{on}}\)) can, in principle, be calculated from physics-based numerical sampling methods for any two molecules under any arbitrary reaction conditions. However, in practice, the problem is often broken down into two steps:

- The process that leads to the formation of encounter complex (EC).

- Molecule-specific interaction dynamics, including conformational changes, that lead to formation of the bound complex (BC) from the encounter complex (EC).

Step 2 must still, in general, be treated using numerical sampling, e.g. all-atom molecular dynamics simulationsm,8 9 10 while step 1 often relies on analytical kinetic rate theories.

The Smoluchowski Diffusion Rate Equation

More than a century ago, Smoluchowski proposed a theory for the kinetics of colloid-coagulation as a diffusion-controlled process.11 Since then, his theory has been further extended to include effects of unsuccessful collisions,12 ions,13 rotational diffusion,14 and asymmetric binding modes.15

According to Smoluchowski theory, the rate at which any two biomolecules encounter each other can be written as:

where \(D = D_A + D_B\) is the sum of diffusion coefficients of the two molecules and \(R = R_A + R_B\) is the sum of their radii. This result is remarkable for several reasons:

- The association rate for two diffusing molecules turns out to be simply proportional to the total size and diffusivity of the molecules.

- It provides the speed limit - a soft upper bound - of the bimolecular reaction rate for any two molecules. The actual association rate is likely to be less than this quantity.

- From a profound theoretical viewpoint, this rate equation establishes a direct connection between physical dynamics and chemical kinetics of biomolecules.

Derivation of Smoluchowski Rate

This last point can be exemplified by deriving Eq. (1) from first-principles. Let us start with the usual derivation of the Smoluchowski rate equation from bulk diffusion.16

We envision the dynamics of the two molecules as isotropic translational diffusion between molecules of \(A\) and \(B\). Without losing any generality, we put ourselves in the reference frame of molecule \(A\), such that \(A\) is held stationary, while \(B\) diffuses until molecules of \(B\) encounter molecules of \(A\). This model suggests that the concentration of (unbound) \(B\) molecules can be described by Fick’s second law:

Where \(D = D_A + D_B\) is again the sum of diffusion coefficients of A and B, while \(C(\mathbf{r}, t)\) represents the concentration of \(B\) at any spatial location \(\mathbf{r} = (r, 𝜃, ø)\) and at any time \(t\). Note that, for the purpose of this problem, we are not interested in the dynamics of the association of \(A\) and \(B\) beyond the encounter complex, or the dynamics of dissociation of \(A\) and \(B\).

When \(A\) and \(B\) are far apart, the concentration of \(B\) is just a constant – the bulk concentration of \(B\) in solution, say \(C(r → ∞, t) = C_0\). As soon as \(A\) and \(B\) encounter each other, we assume that they have reached the EC. Thus, we install an absorbing boundary condition at the encounter cross-section, e.g. \(r = R = R_A + R_B\) or the sum of the radii of \(A\) and \(B\), such that \(C(r = R, t) = 0\).

At steady state, the rate of change of \(C(r, t)\) or the left hand side of Eq. (2) goes to zero. In other words, the concentration distribution of \(B\) becomes constant with respect to time, i.e. \(C(r, t → ∞) → C(r)\). Thus, Eq. (2) reduces to:

In order to solve this equation analytically, we exploit the spherical symmetry of the problem – collision of \(A\) and \(B\) in any orientation with respect to each other leads to the formation of the encounter complex and, thus, the Laplacian in Eq. (3) consists of only the radial direction in spherical coordinates:

It is easy to verify that the solution to Eq. (4) that satisfies the necessary boundary conditions can be written as:

Now that we have solved for the concentration distribution profile of \(B\), we can use this solution to extract the rate of encounter with \(A\).

The flux of \(B\) encountering \(A\), or the number of collisions between \(A\) and \(B\) per unit time per unit area, is given by Fick’s first law:

Plugging Eq. (5) into Eq. (6), we get the steady state flux of \(B\) encountering \(A\):

The negative sign here simply denotes the direction of the flux in the radial coordinate \(ȓ\), i.e. towards the molecules of \(A\) or, equivalently, towards the origin. The total flux over the entire cross-section of the encounter, i.e. the total number of collisions between \(A\) and \(B\) per unit time, can be obtained by computing the surface integral:

For the simplest scenario of a spherical encounter cross-section with radius \(r = R\), \(∮d\mathbf{S} = 4πR^2 ȓ\) and the total flux turns out to be:

Finally, the rate of this encounter is simply the flux per unit bulk concentration of \(B\), i.e.

References

-

Vauquelin, G. (2016). Effects of target binding kinetics on in vivo drug efficacy: \(k_{\text{off}}, k_{\text{on}}\), and rebinding. British Journal of Pharmacology, 173(15), 2319-2334. ↩

-

Klipp, E., & Liebermeister, W. (2006). Mathematical modeling of intracellular signaling pathways. BMC Neuroscience, 7, 1-16. ↩

-

Bansal, L., Nichols, E. M., et al. (2022). Mathematical modeling of complement pathway dynamics for target validation and selection of drug modalities for complement therapies. Frontiers in Pharmacology, 13, 855743. ↩

-

Eigen, M. (1974). Diffusion control in biochemical reactions. Quantum Statistical Mechanics in the Natural Sciences. ↩

-

Bell, G. I. (1978). Models for the specific adhesion of cells to cells. Science, 200(4342), 618-627. ↩

-

Gabdoulline, R. R., & Wade, R. C. (1999). On the protein-protein diffusional encounter complex. Journal of Molecular Recognition, 12(4), 226-234. ↩

-

Tang, C., Iwahara, J., & Clore, G. M. (2006). Visualization of transient encounter complexes in protein-protein association. Nature, 444(7117), 383-386. ↩

-

Tiwary, P., et al. (2015). Kinetics of protein-ligand unbinding: Predicting pathways, rates, and rate-limiting steps. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 112(5), E386-E391. ↩

-

Plattner, N., et al. (2017). Complete protein-protein association kinetics in atomic detail revealed by molecular dynamics simulations and Markov modeling. Nature Chemistry, 9(10), 1005-1011. ↩

-

Tang, Z., et al. (2020). Transient states and barriers from molecular simulations and the milestoning theory. Journal of Chemical Theory and Computation, 16(3), 1882-1895. ↩

-

Smoluchowski, M. V. (1917). Mathematical theory of the kinetics of the coagulation of colloidal solutions. Z. Phys. Chem., 92, 129-168. ↩

-

Sveshnikoff, B. (1935). On the theory of photochemical reactions and chemiluminescence in solutions. Acta Physicochim. USSR, 3, 257-268. ↩

-

Debye, P. (1942). Reaction rates in ionic solutions. Transactions of the Electrochemical Society, 82(1), 265. ↩

-

Shoup, D., Lipari, G., & Szabo, A. (1981). Diffusion-controlled bimolecular reaction rates. The effect of rotational diffusion and orientation constraints. Biophysical Journal, 36(3), 697-714. ↩

-

Schlosshauer, M., & Baker, D. (2002). A general expression for bimolecular association rates with orientational constraints. Journal of Physical Chemistry B, 106(46), 12079-12083. ↩

-

Altan-Bonnet, G., Mora, T., & Walczak, A. M. (2020). Quantitative immunology for physicists. Physics Reports, 849, 1-83. ↩