Memory Retention through Metamorphosis

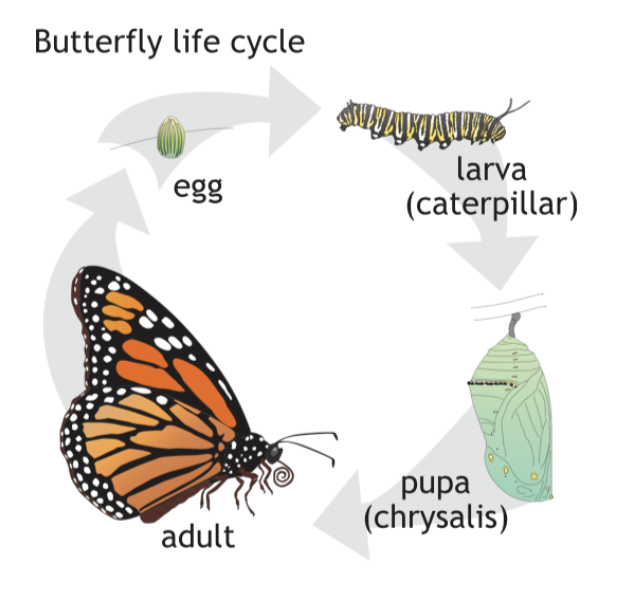

Metamorphosis in insects—such as butterflies, moths, and flies—involves dramatic changes, including extensive reorganization of the nervous system. Remarkably, some memories formed during the larval stage persist despite this significant neural transformation. This fascinating phenomenon raises fundamental questions about how memories can be retained when neural circuits undergo drastic remodeling.

Holometabolous insects undergo complete metamorphosis, dramatically reshaping their nervous system. Many larval neurons degenerate, synapses are pruned, and new adult-specific neurons emerge. For example, in Drosophila melanogaster, mushroom bodies—structures critical for learning and memory—undergo significant remodeling. Larval mushroom body neurons prune their connections extensively during pupation, essentially “resetting” synaptic circuits to form the adult brain.2

Given this extensive rewiring, it’s surprising that some memories formed during the larval stage can persist into adulthood.

Studies by Tully and Quinn3 first demonstrated memory retention across metamorphosis in fruit flies. Larvae conditioned to associate an odor with a mild shock continued to avoid the odor after metamorphosis into adults. Similarly, Blackiston et al.4 showed tobacco hornworm moths (Manduca sexta) retained aversive odor memories learned as caterpillars—but only if training occurred in later larval stages.

How can memories persist through such extensive neural reorganization?

-

Certain neurons survive the metamorphosis process intact. These neurons might act as memory “carriers,” retaining molecular or cellular changes linked to memories formed during the larval stage. However, research indicates extensive pruning of synapses, making this explanation insufficient on its own.2

-

Studies suggest memories might also persist at molecular or epigenetic levels. Long-lasting molecular changes—such as altered RNA expression patterns—have been reported in earlier research with beetles trained during larval stages.5 These molecular “footprints” could potentially help re-establish neural connections related to the original memory during adult development.

-

The stage of development when the memory forms is crucial. Blackiston et al.4 found that memories formed late in larval development are more likely to persist, possibly because neural circuits formed later undergo less drastic pruning, allowing memory traces to survive the metamorphic transition.

Despite evidence that certain associative memories can persist, the precise neural and molecular mechanisms remain elusive. Recent studies2 using advanced genetic labeling methods revealed extensive rewiring during metamorphosis with minimal anatomical continuity. This suggests that retained memories might be re-encoded at the molecular or cellular level rather than preserved through stable connections.

Memory retention through metamorphosis offers adaptive advantages. For instance, an insect that remembers aversive experiences from its larval stage could avoid similar threats as an adult, influencing behaviors like egg-laying site selection. This capability reflects an evolutionary strategy balancing neural plasticity and memory persistence.

References

-

https://www.floridamuseum.ufl.edu/educators/resource/butterfly-life-cycle/ ↩

-

Truman, J. W., Price, J., Miyares, R. L., & Lee, T. (2023). Metamorphosis of memory circuits in Drosophila reveals a strategy for evolving a larval brain. Elife, 12, e80594. ↩ ↩2 ↩3

-

Tully, T., & Quinn, W. G. (1985). Classical conditioning and retention in normal and mutant Drosophila melanogaster. Journal of Comparative Physiology A, 157(2), 263-277. ↩

-

Blackiston, D. J., Silva Casey, E., & Weiss, M. R. (2008). Retention of memory through metamorphosis: can a moth remember what it learned as a caterpillar? PLoS ONE, 3(3), e1736. ↩ ↩2

-

Punzo, F., & Malatesta, R. J. (1988). Brain RNA synthesis and the retention of learning through metamorphosis in Tenebrio obscurus (Insecta: Coleoptera). Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology. A, Comparative Physiology, 91(4), 675-678. ↩