On the genetic evidence for making designer babies

The term “Eugenics” was coined by the English polymath Francis Galton in 1883.1 He defined it as “the science of improving stock”, derived from the Greek word eugenes, meaning “good in stock” or “hereditarily endowed with noble qualities”. The central tenet of the Eugenics theory is that the human race can be improved through selective breeding or other means. We now know that this theory had devastating consequences in society, promoting racism, ableism, inequality, colonialism, antisemitism, and xenophobia; ultimately inspiring policies like forced sterilization and genocide in Nazi Germany.2 I personally acquired a great amount of knowledge and perspective on this topic from Siddhartha Mukherjee’s The Gene: An Intimate History.3

Beyond the moral, ideological, political, and social implications, we also think the Eugenics theory is scientifically inaccurate. Briefly,

- What human traits are “desirable” can be highly subjective. Moreover, a genetic variation may be associated with more than one trait. This makes selection toward “improved” qualities complex and subjective. An example of this may be the case of Stephen Hawking, arguably the most famous physicist of recent times, who was diagnosed with ALS early in his life,4 but went on to unravel the physics of black holes.5

- Eugenics relies on the assumption that there is a clear separation between human races. In the post-Human Genome era, we have evidence to suggest that genetic variation in human populations can indeed be attributed to geographical locations and ancestry, but these variations are loosely associated with the social definitions of “race” and their distributions overlap between populations.6 Thus, selective breeding based on appearance and other racial characteristics is doomed to fail.

- Eugenics assumes that certain behavioral traits, like personality and intelligence, are genetically determined and static across human lifespan, which turns out to be false.7

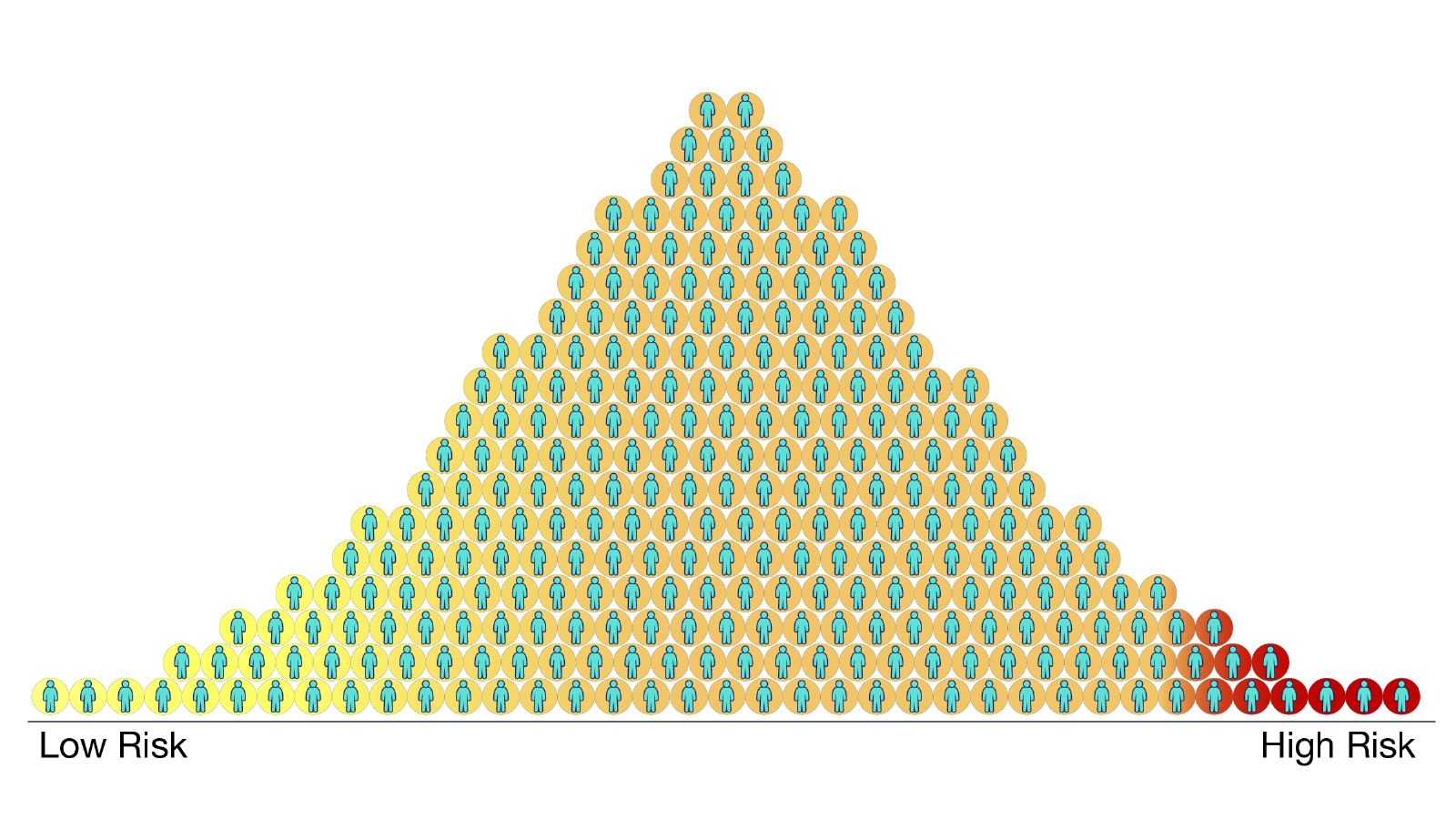

In contrast, modern genetic risk scores build on data from Genome-Wide Association Studies (GWAS), as they became more common in the last two decades.8 The purpose of these scores is to assess the relative risk of a phenotype or outcome, e.g. a disease, in an individual based on their genetic identity. It is important to understand that these scores, by design, reflect the probability of genetic predisposition, given the prior distribution of genotype-phenotype relationships sampled from human populations in specific studies:9

Pre-implantation genetic screening for monogenic diseases and large chromosomal abnormalities or structural rearrangements have been around for more than 30 years and are widely used in clinics around the world.10 They have proved to be a valuable tool for early detection and screening for rare genetic diseases.11 More recently, there has been great scientific interest in Polygenic Risk Scores (PRS)12 that aim to estimate the risk of more common polygenic diseases, e.g. Breast Cancer,13 Multiple Sclerosis,14 Inflammatory Bowel Disease,15 Coronary Artery Disease,16 Type II Diabetes,17 and Obesity18 among others.19

PRS have potential to become valuable tools for understanding mechanisms of these complex diseases, identifying clinically relevant targets and biomarkers, and patient selection for clinical trials. Moreover, improving the predictive capacity of these scores and collecting data to improve representation, can allow converting these scores to an absolute scale,20 providing a more simplified and intuitive interpretation of individual risk.

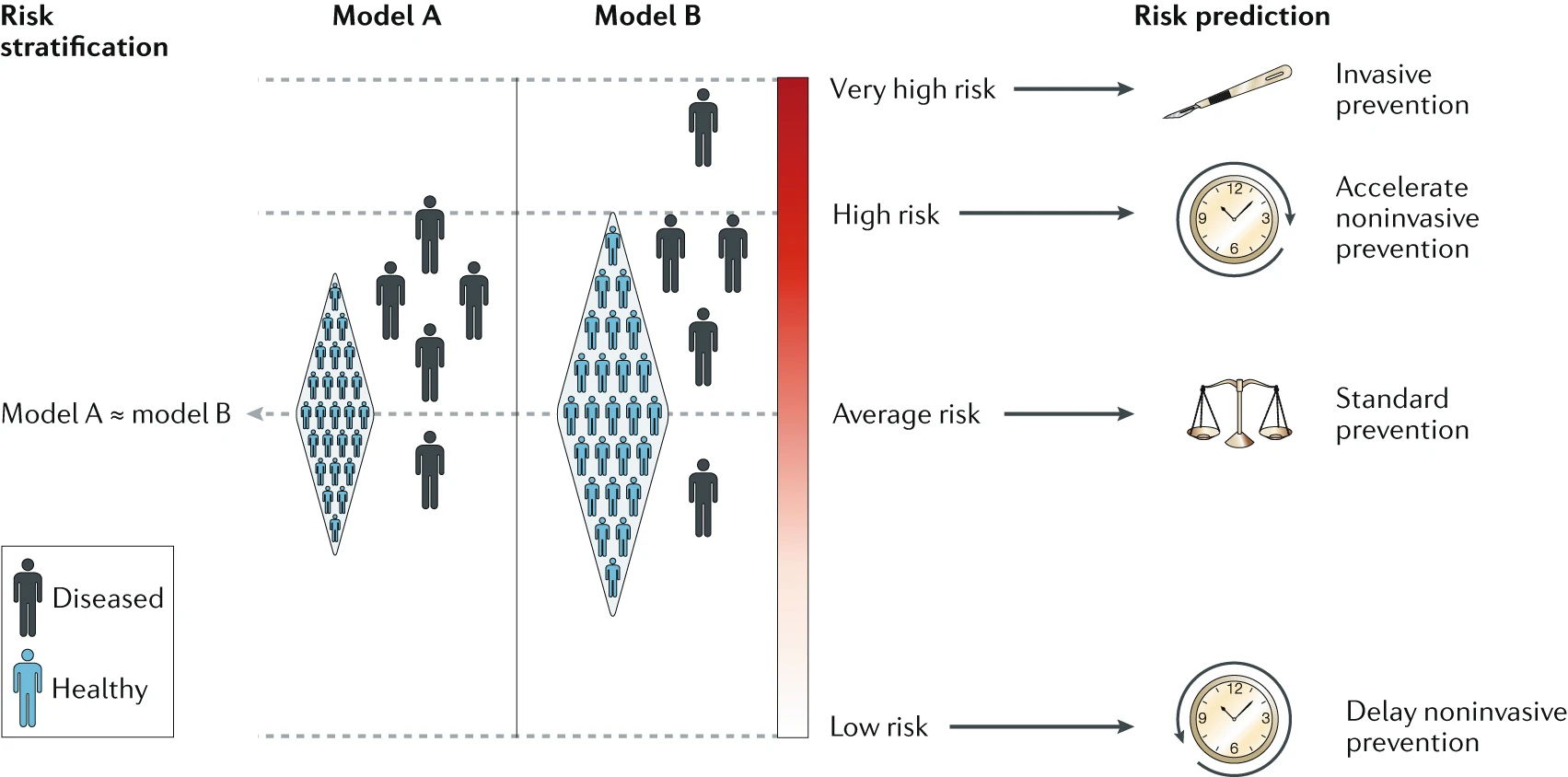

However, the GWAS-based PRS available today have limited predictive accuracy and utility,21 partly because of the way in which they are calculated and evaluated. In particular, PRS are typically calculated by accummulating effect sizes from a number of risk alleles, as identified in a patient vs healthy population, and evaluated using the area under curve (AUC) of the receiver operating characteristic (ROC).22 Importantly, AUC is a population-level metric that is most appropriate for a diagnostic test, the primary purpose of which is the separation of diseased from non-diseased individuals. Yet, the relevant use case for genetic risk information is prognosis, a prediction of the likelihood that a certain outcome, such as the onset of disease, will occur in each individual or embryo.22

The above figure is taken from Torkamani et al.22 depicting the utility of risk information for population-level risk stratification (ordering individuals by risk) and prediction of individual-level and group-level disease susceptibility (absolute risk of disease). The figure illustrates how two population models A and B with similar AUC estimates and, hence, similar PRS performance can lead to different conclusions in their utility. This, in my view, is a strong argument against using the current generation of GWAS-based PRS for pre-implantation genetic screening.

It is not inconceivable that these limitations in accuracy and evaluation methods will be overcome in the future – using multi-ancestry analyses,23 ensemble approaches,24 clinical records integration,25 deep learning,26 and workflow standardization27 – and interpretation of PRS will become more robust and reliable for some polygenic diseases. In that future, I suspect embryo-screening on the basis of PRS will become more widely accepted, though it will likely remain a matter of personal preference, with possibly politically charged sentiments (as we have for abortion rights today in the US).

One issue that I did not touch till now is the use of polygenic scores to screen for embryos beyond disease risk – to optimize certain polygenic characteristics like height, personality, and IQ. It turns out that GWAS-based polygenic scores for these traits have also been developed,28 29 30 though their performance and interpretation are similarly impaired as PRS for other polygenic diseases. It is possible that improved models could be developed in the future for predicting these traits, but their widespread use in embryo screening will likely be more controversial than for polygenic diseases.

References:

-

Galton, F. (1883). Inquiries into human faculty and its development. Macmillan. ↩

-

Spiegel, A. M. (2019). The Jeremiah Metzger lecture: A brief history of eugenics in America: Implications for medicine in the 21st century. Transactions of the American Clinical and Climatological Association, 130, 216. ↩

-

Mukherjee, S. (2016). The Gene: An Intimate History. Scribner. New York, NY. ↩

-

Westeneng, H. J., Al-Chalabi, A., Hardiman, O., Debray, T. P., & van den Berg, L. H. (2018). The life expectancy of Stephen Hawking, according to the ENCALS model. The Lancet Neurology, 17(8), 662-663. ↩

-

Hawking, S. W. (1975). Particle creation by black holes. Communications in mathematical physics, 43(3), 199-220. ↩

-

Jorde, L. B., & Wooding, S. P. (2004). Genetic variation, classification and’race’. Nature genetics, 36(Suppl 11), S28-S33. ↩

-

Chakravarti, A. (2015). Perspectives on human variation through the lens of diversity and race. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology, 7(9), a023358. ↩

-

Igo Jr, R. P., Kinzy, T. G., & Cooke Bailey, J. N. (2019). Genetic risk scores. Current protocols in human genetics, 104(1), e95. ↩

-

https://www.genome.gov/Health/Genomics-and-Medicine/Polygenic-risk-scores ↩

-

Du, R. Q., Zhao, D. D., Kang, K., Wang, F., Xu, R. X., Chi, C. L., … & Liang, B. (2023). A review of pre-implantation genetic testing technologies and applications. Reproductive and Developmental Medicine, 7(01), 20-31. ↩

-

https://www.acog.org/clinical/clinical-guidance/committee-opinion/articles/2020/03/preimplantation-genetic-testing ↩

-

Ma, Y., & Zhou, X. (2021). Genetic prediction of complex traits with polygenic scores: a statistical review. Trends in Genetics, 37(11), 995-1011. ↩

-

Mavaddat, N., Michailidou, K., Dennis, J., Lush, M., Fachal, L., Lee, A., … & MacInnis, R. J. (2019). Polygenic risk scores for prediction of breast cancer and breast cancer subtypes. The American Journal of Human Genetics, 104(1), 21-34. ↩

-

Wang, J. H., Pappas, D., De Jager, P. L., Pelletier, D., de Bakker, P. I., Kappos, L., … & Oksenberg, J. R. (2011). Modeling the cumulative genetic risk for multiple sclerosis from genome-wide association data. Genome medicine, 3, 1-11. ↩

-

Khera, A. V., Klarin, D., & Kathiresan, S. (2019). U.S. Patent Application No. 16/510,834. ↩

-

King, A., Wu, L., Deng, H. W., Shen, H., & Wu, C. (2022). Polygenic risk score improves the accuracy of a clinical risk score for coronary artery disease. BMC medicine, 20(1), 385. ↩

-

Ge, T., Irvin, M. R., Patki, A., Srinivasasainagendra, V., Lin, Y. F., Tiwari, H. K., … & Karlson, E. W. (2022). Development and validation of a trans-ancestry polygenic risk score for type 2 diabetes in diverse populations. Genome Medicine, 14(1), 70. ↩

-

Torkamani, A., & Topol, E. (2019). Polygenic risk scores expand to obesity. Cell, 177(3), 518-520. ↩

-

Ibanez, L., Farias, F. H., Dube, U., Mihindukulasuriya, K. A., & Harari, O. (2019). Polygenic risk scores in neurodegenerative diseases: a review. Current Genetic Medicine Reports, 7, 22-29. ↩

-

Pain, O., Gillett, A. C., Austin, J. C., Folkersen, L., & Lewis, C. M. (2022). A tool for translating polygenic scores onto the absolute scale using summary statistics. European Journal of Human Genetics, 30(3), 339-348. ↩

-

Murray, G. K., Lin, T., Austin, J., McGrath, J. J., Hickie, I. B., & Wray, N. R. (2021). Could polygenic risk scores be useful in psychiatry?: a review. JAMA psychiatry, 78(2), 210-219. ↩

-

Torkamani, A., Wineinger, N. E., & Topol, E. J. (2018). The personal and clinical utility of polygenic risk scores. Nature Reviews Genetics, 19(9), 581-590. ↩ ↩2 ↩3

-

He, Y., Lu, W., Jee, Y. H., Wang, Y., Tsuo, K., Qian, D. C., … & Martin, A. R. (2024). Multi-trait and multi-ancestry genetic analysis of comorbid lung diseases and traits improves genetic discovery and polygenic risk prediction. medRxiv. ↩

-

Lerga-Jaso, J., Terpolovsky, A., Novković, B., Osama, A., Manson, C., Bohn, S., … & Yazdi, P. G. (2025). Optimization of multi-ancestry polygenic risk score disease prediction models. Scientific Reports, 15(1), 1-19. ↩

-

Khunsriraksakul, C., Li, Q., Markus, H., Patrick, M. T., Sauteraud, R., McGuire, D., … & Liu, D. J. (2023). Multi-ancestry and multi-trait genome-wide association meta-analyses inform clinical risk prediction for systemic lupus erythematosus. Nature communications, 14(1), 668. ↩

-

Badré, A., Zhang, L., Muchero, W., Reynolds, J. C., & Pan, C. (2021). Deep neural network improves the estimation of polygenic risk scores for breast cancer. Journal of Human Genetics, 66(4), 359-369. ↩

-

Taha, A., Matt McCrary, J., van Rooij, J., Lahousse, L., Paoletti, F., Pascucci, E., … & Boccia, S. (2024). Clinical recommendations for polygenic risk score-enhanced breast cancer screening: Can. Heal project. European Journal of Public Health, 34(Supplement_3), ckae144-706. ↩

-

Lu, T., Forgetta, V., Wu, H., Perry, J. R., Ong, K. K., Greenwood, C. M., … & Richards, J. B. (2021). A polygenic risk score to predict future adult short stature among children. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 106(7), 1918-1928. ↩

-

Socrates, A. J., Mullins, N., Gur, R. C., Gur, R. E., Stahl, E., O’Reilly, P. F., … & Velthorst, E. (2024). Polygenic risk of social isolation behavior and its influence on psychopathology and personality. Molecular Psychiatry, 29(11), 3599-3606. ↩

-

Genç, E., Schlüter, C., Fraenz, C., Arning, L., Metzen, D., Nguyen, H. P., … & Ocklenburg, S. (2021). Polygenic scores for cognitive abilities and their association with different aspects of general intelligence—a deep phenotyping approach. Molecular Neurobiology, 58(8), 4145-4156. ↩