A drug target liver injury risk score

Drug-induced liver injury (DILI) continues to be a leading cause of drug failure in clinical trials and post-marketing withdrawals.1 The liver’s central role in drug metabolism, combined with its complex cellular architecture and diverse metabolic pathways, makes it particularly vulnerable to drug-induced damage. Traditional approaches to DILI prediction have relied heavily on animal models and in vitro assays, but these methods have limited predictive power for human outcomes.2

The advent of large-scale genomic and proteomic datasets has opened new possibilities for computational approaches to DILI risk assessment. In particular, integration of drug-target interaction data, pathway information, and clinical outcomes has enabled the development of more sophisticated risk prediction models. Here, I present a computational framework for assessing DILI risk at the drug target level, leveraging multiple data sources to create interpretable risk scores that can guide target prioritization in drug discovery.

Definition

The core insight of this approach is that DILI risk can be assessed through two complementary mechanisms: direct evidence and network guilt-by-association. Direct evidence captures the known DILI risk associated with drugs that target a specific gene, while network guilt-by-association leverages the biological principle that genes connected in cellular networks often share functional properties, including susceptibility to drug-induced damage.

Direct Evidence Computation

For each drug target, we compute direct DILI evidence based on the FDA’s DILIrank dataset, which categorizes drugs according to their DILI concern level.3 The direct evidence score for a target \(T\), mapped to each drug using Opentargets data,4 is calculated as:

\[\text{Direct Evidence}(T) = \frac{\sum_{d \in D_T} w_d}{\sum_{d \in D_T}}\]where \(D_T\) is the set of drugs targeting \(T\) and \(w_d\) is the DILI severity weight for drug \(d\).

This approach captures the empirical observation that targets with more high-risk drugs are themselves more likely to be associated with DILI. For example, cytochrome P450 enzymes (CYP3A4, CYP2D6) show high direct evidence scores due to their involvement in the metabolism of numerous hepatotoxic compounds.5

Network Guilt-by-Association

The network component leverages Pathway Commons data to identify targets that are functionally connected to known DILI-associated genes.6 The network score for a target \(T\) is computed as:

\[\text{Network Score}(T) = \sum_{N \in \mathcal{N}(T)} \text{Direct Evidence}(N)\]where \(\mathcal{N}(T)\) represents the set of network neighbors of target \(T\).

This approach is based on the biological principle that genes involved in related cellular processes often share similar drug sensitivity profiles. For instance, targets in the same metabolic pathway or gene complex may exhibit similar DILI risk profiles.

Combined Risk Score

The final DILI risk score combines both components:

\[\text{DILI Risk Score}(T) = \alpha \cdot \text{Direct Evidence}(T) + (1-\alpha) \cdot \text{Network Score}(T)\]where \(\alpha\) is a weighting parameter (typically set to 0.5) that balances the contribution of direct evidence versus network guilt-by-association.

Validation Metrics

Approval rates are computed per target as the proportion of approved drugs among all drugs targeting that gene. For each target \(T\):

\[\text{Approval Rate}(T) = \frac{\text{Number of approved drugs targeting } T}{\text{Total number of drugs targeting } T}\]Withdrawal rates are computed per target as the proportion of withdrawn drugs among all drugs targeting that gene:

\[\text{Withdrawal Rate}(T) = \frac{\text{Number of withdrawn drugs targeting } T}{\text{Total number of drugs targeting } T}\]Both metrics are calculated using deduplicated drug-target pairs to ensure consistency with the risk scoring process. Drug approval and withdrawal status is obtained from OpenFDA data,7 which tracks the regulatory history of pharmaceutical compounds. A drug is considered “approved” if it has received FDA approval for any indication, and “withdrawn” if it has been removed from the market due to safety concerns, including liver injury.

Results and Interpretation

We divided 518 drug targets into 3 buckets:

Risk Distribution

- Low Risk: 173 targets (90.1%)

- Medium Risk: 173 targets (7.1%)

- High Risk: 172 targets (2.8%)

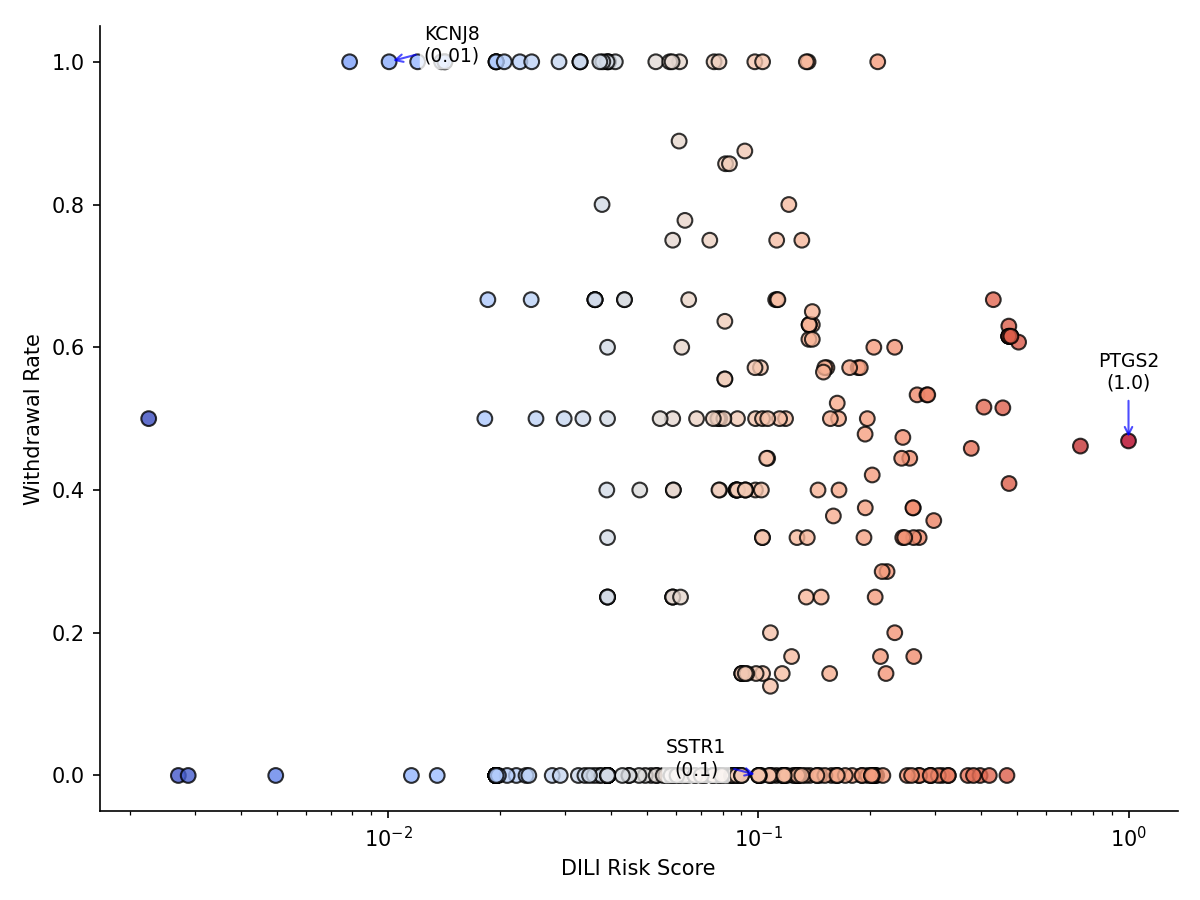

Figure 1: DILI risk score vs. drug withdrawal rate for 518 targets. Higher DILI risk targets correlate (weakly) with higher withdrawal rates (r = 0.025), indicating that targets associated with more hepatotoxic drugs are slightly more likely to have drugs withdrawn from the market due to safety concerns.

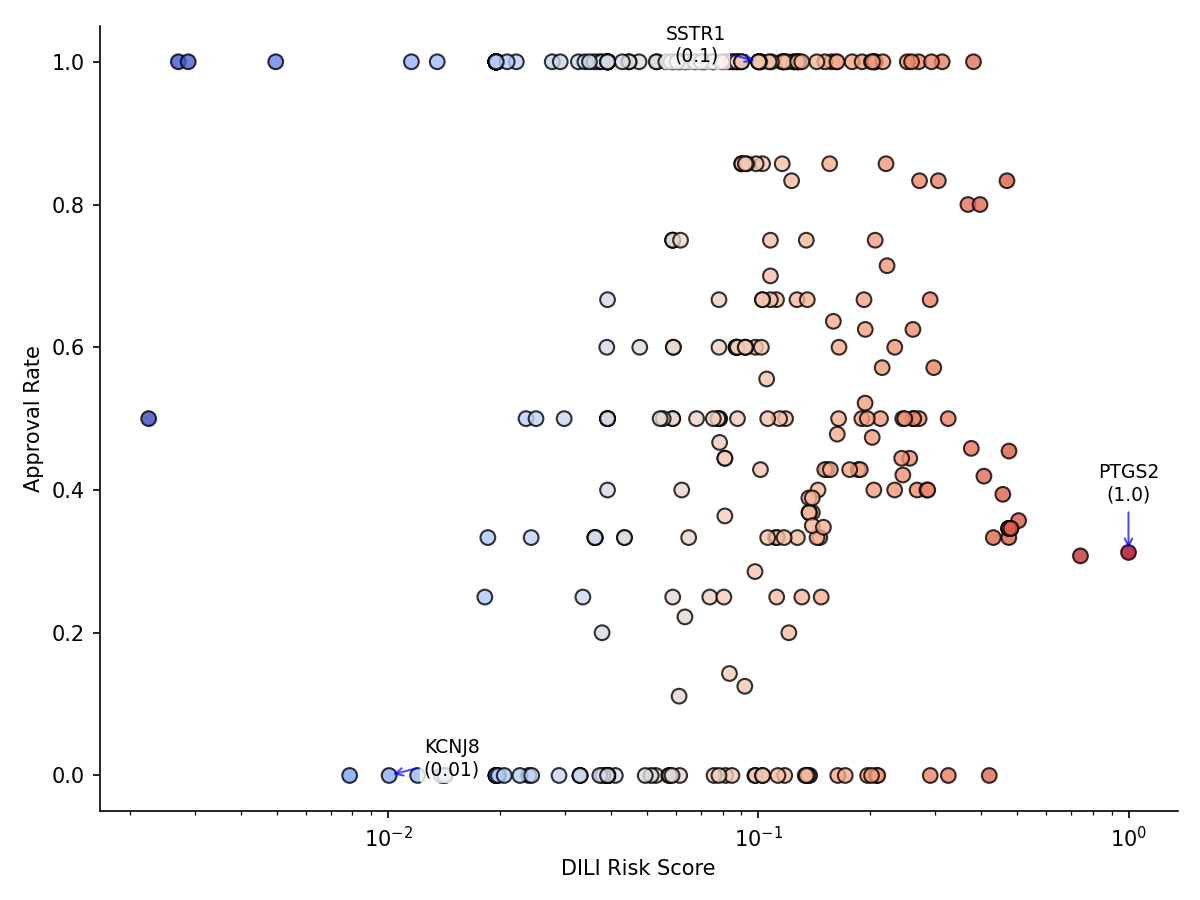

Figure 2: DILI risk score vs. drug approval rate for 518 targets. Higher DILI risk targets correlate (weakly) with lower approval rates (r = -0.063), indicating that targets associated with more hepatotoxic drugs have slightly fewer drugs successfully approved by FDA.

Top High-Risk Targets

The highest-risk targets identified using this approach are:

- PTGS2 (COX-2): Risk score 1.0 (High)

- Associated with 32 drugs – 10 approved/15 withdrawn

- PTGS1 (COX-1): Risk score 0.7 (High)

- Associated with 26 drugs – 8 approved/12 withdrawn

- SCN5A (Sodium channel): Risk score 0.5 (High)

- Associated with 28 drugs – 10 approved/17 withdrawn

Some of these results align with known DILI mechanisms. COX enzymes are well-established targets for NSAIDs, which are known to cause liver injury in susceptible individuals. Sodium channels are also implicated in drug-induced toxicity.8

Limitations and Future Directions

The current approach has several limitations:

- Data Quality: The approach relies on the quality and completeness of the underlying datasets. Missing drug-target interactions or incomplete DILI classifications reduce reliability of the risk score.

- Mechanistic Complexity: DILI involves complex interactions between drug properties, target characteristics, and patient factors. A target-level approach is just one piece of this complexity.

- Temporal Dynamics: The current approach uses static data, but DILI risk may vary over time as new drugs are developed and clinical experience accumulates.

- Validation Scope: The validation approach focuses on aggregate withdrawal/approval rates, but individual drug outcomes may vary significantly.

Future work could address these limitations through:

- Multi-omic Integration: Incorporating transcriptomic, proteomic, and metabolomic data to capture dynamic cellular responses

- Patient-Specific Modeling: Accounting for genetic, demographic, and clinical factors that influence individual DILI risk

- Temporal Analysis: Tracking how DILI risk profiles evolve as new drugs and clinical data become available

- Mechanistic Validation: Experimental validation of predicted high-risk targets using in vitro and in vivo models

Clinical and Drug Discovery Implications

Despite its limitations, this computational framework provides several valuable insights for drug discovery and development:

- Target Prioritization: The risk scores can help prioritize targets for drug development, with higher-risk targets requiring more extensive preclinical safety assessment.

- Safety Monitoring: For drugs targeting high-risk genes, enhanced clinical monitoring for liver function may be warranted.

- Drug Repurposing: The framework can identify existing drugs that target high-risk genes, potentially flagging candidates for enhanced safety monitoring.

- Mechanistic Insights: The network component can reveal unexpected connections between targets and DILI mechanisms, potentially uncovering new therapeutic targets for DILI prevention.

Conclusion

The computational framework presented here represents a step toward more systematic assessment of DILI risk at the target level. By integrating multiple data sources and employing both direct evidence and network guilt-by-association approaches, the method provides interpretable risk scores that align with biological expectations and clinical outcomes.

While the current implementation has limitations, it demonstrates the potential for computational approaches to complement traditional experimental methods in drug safety assessment. As datasets grow and methods improve, such approaches may become increasingly valuable for guiding drug discovery and development decisions.

The framework is implemented as an open-source pipeline with a web application for real-time risk score checking, making it accessible to researchers and drug developers worldwide.

References:

-

Björnsson, E. S. (2015). Drug-induced liver injury: an overview over the most critical compounds. Archives of toxicology, 89(3), 327-334. ↩

-

Olson, H., Betton, G., Robinson, D., Thomas, K., Monro, A., Kolaja, G., … & Heller, A. (2000). Concordance of the toxicity of pharmaceuticals in humans and in animals. Regulatory toxicology and pharmacology, 32(1), 56-67. ↩

-

Chen, M., Suzuki, A., Borlak, J., Andrade, R. J., & Lucena, M. I. (2015). Drug-induced liver injury: Interactions between drug properties and host factors. Journal of hepatology, 63(2), 503-514. ↩

-

Ochoa, D., Hercules, A., Carmona, M., Suveges, D., Gonzalez-Uriarte, A., Malangone, C., … & Papatheodorou, I. (2021). Open Targets Platform: supporting systematic drug–target identification and prioritisation. Nucleic Acids Research, 49(D1), D1302-D1310. ↩

-

Zanger, U. M., & Schwab, M. (2013). Cytochrome P450 enzymes in drug metabolism: regulation of gene expression, enzyme activities, and impact of genetic variation. Pharmacology & Therapeutics, 138(1), 103-141. ↩

-

Rodchenkov, I., Babur, O., Luna, A., Aksoy, B. A., Wong, J. V., Fong, D., … & Sander, C. (2020). Pathway Commons 2019 Update: integration, analysis and exploration of pathway data. Nucleic acids research, 48(D1), D489-D497. ↩

-

Zarin, D. A., Tse, T., Williams, R. J., Califf, R. M., & Ide, N. C. (2011). The ClinicalTrials. gov results database—update and key issues. New England Journal of Medicine, 364(9), 852-860. ↩

-

Watkins, P. B., Kaplowitz, N., Slattery, J. T., Colonese, C. R., Colucci, S. V., Stewart, P. W., & Harris, S. C. (2006). Aminotransferase elevations in healthy adults receiving 4 grams of acetaminophen daily: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA, 296(1), 87-93. ↩