Sarepta's Elevidys debacle: Lessons for data-driven drug development and biotech investments

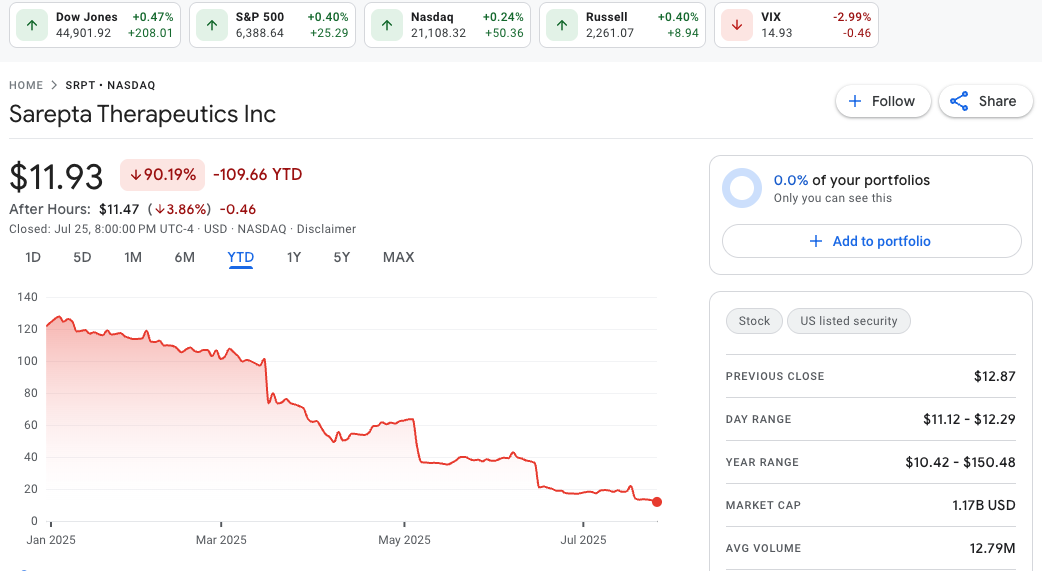

Sarepta Therapeutics ($SRPT) stock price has taken a nosedive this year, due to multiple deaths associated with its flagship gene therapy, Elevidys; appointment of Vinay Prasad, a vocal critic of the Accelerated Approval pathway, as the head of FDA’s Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research (CBER); rejection from European Medicines Agency; and a rare move by the company to defy, and later bow down to, FDA’s request for pulling Elevidys from the market.

Figure 1: Sarepta stock price trend YTD from Google Finance.

Accelerated Approval

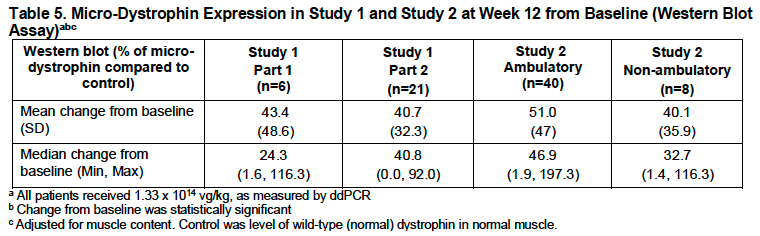

Elevidys, or delandistrogene moxeparvovec, was first approved in 2023 in ambulatory patients aged 4-5 to treat Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy (DMD), a rare genetic condition that leads to muscle weakness, motor dysfunction, difficulty breathing, and eventually death.1 Later, it was approved for both non-ambulatory and ambulatory individuals over the age of 4. Notably, the approval, in both cases, hinged on a surrogate efficacy endpoint: increased expression of microdystrophin levels vs baseline (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Table 5 from Elevidys Prescription Label issued by FDA (Source). Study 1 [NCT03769116] was double-bind placebo-controlled and Study 2[NCT04626674] was open-label. In both cases, significant expression of microdystrophin protein levels was observed in muscle biopsies taken after 12 weeks from treatment infusion vs prior to treatment as baseline.

The logical reason for using this biomarker is that Elevidys is an adeno-associated viral (AAV) capsid encapsulated vector genome, consisting of a microdystrophin expressing cassette.2 The genetic cause of DMD is mutations in the DMD gene, the largest known human gene,3 that encodes for expression of dystrophin in muscle as well as other cells. Due to payload size restrictions imposed by the AAV delivery vehicle, the trans-gene encoding Elevidys microdystrophin is a mutant shortened form of DMD.4 If patients infused with Elevidys express microdystrophin in their muscles, it is the first sanity check for the gene therapy’s functional efficacy.

Lack of Efficacy evidence and safety risks

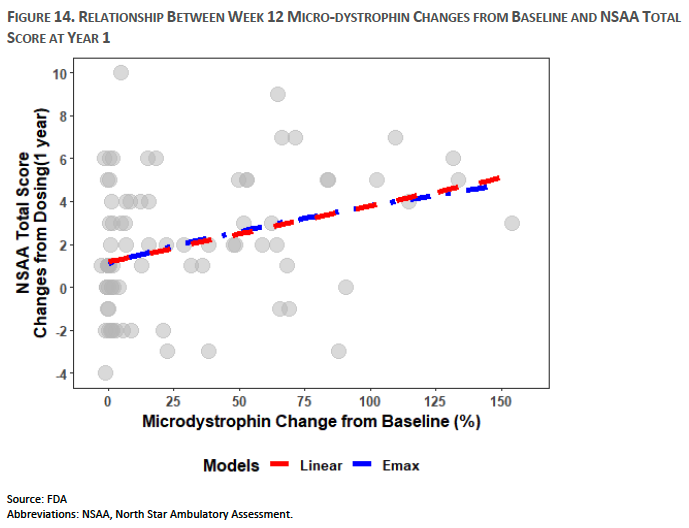

However, as noted in the materials from an FDA Advisory Committee Meeting held in May 2023, the evidence to suggest that this surrogate efficacy endpoint correlates with clinical benefit in DMD is barely significant (Figure 3). Specifically, North Star Ambulatory Assessment (NSAA) is a 17-item rating scale commonly used to measure motor function in ambulatory subjects with DMD. NSAA evaluates abilities including standing, walking, arising from a chair, standing on one leg, climbing onto, and descending from a box step, transitioning from the supine to sitting position, rising from the floor, jumping, hopping, and running. These tasks are performed by the subject in a clinical setting, according to instructions administered by a health care professional.5

Figure 3: FDA’s Cellular, Tissue, and Gene Therapies Advisory Committee Meeting on May 12, 2023 (Source). Analysis based on pooled data from multiple clinical studies.

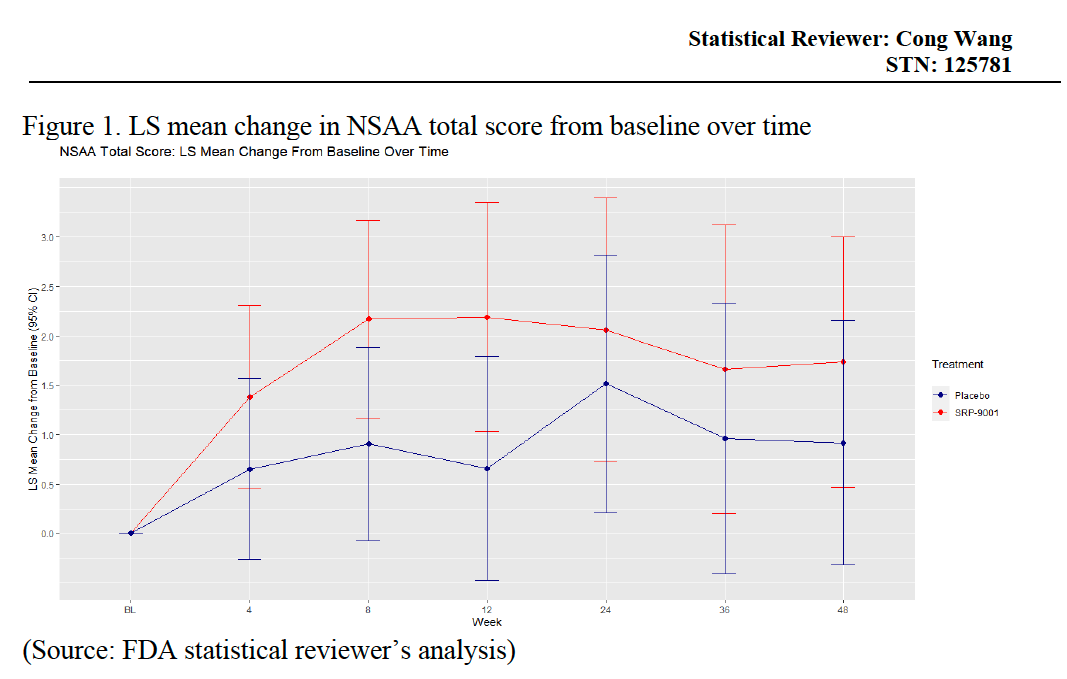

Moreover, direct NSAA assessment in clinical trials showed no statistically significant improvement over placebo.

Figure 4: Statistical Review of Elevidys (Source). The Least Squares (LS) mean change in NSAA Total score from baseline to Week 48 were 1.74 ± 0.62 and 0.92 ± 0.61 for treatment and placebo groups respectively. Thus, the treatment difference was found to be not statistically significant.

Note that, in clinical trials for Elevidys, there were indications of severe treatment-related adverse events, including serious acute liver injury, though there were no deaths associated with it. However, this has been a known side effect of AAV-related gene therapy products.6 Hence, once the therapy was widely available, there were bound to be fatalaties related to extreme cases of liver injury caused by Elevidys.

Lessons learnt

Given such lack of evidence of efficacy and potential serious safety risks, why did the FDA approve Elevidys in the first place? Indeed, a recent paper7 provides a scathing review of this decision by questioning FDA’s present standards:

The FDA’s decision to approve delandistrogene moxeparvovec broadly despite these significant limitations in the evidence base raises serious concerns about the agency’s adherence to its own standards for substantial evidence of effectiveness. The overruling of multiple review teams’ recommendations for a Complete Response letter by the CBER Director undermines confidence in the FDA’s rigorous review process and may set a dangerous precedent for future drug approvals.

In my view, this story has several important lessons:

-

The bar for developing new drugs is high, as it should be. If we don’t hold ourselves to higher standards, we are literally putting innocent lives at risk.

-

The FDA needs better, more objective, criteria for approving drugs for every patient population. Elevidys’s efficacy limitations and safety risks should have impeded its approval, despite the unmet needs in DMD. On the other hand, if the patients are aware and satisfied with the risk profile, despite fatal consequences, there is no need for the FDA to pull the drug from the market on the grounds of deaths due to acute liver failure.

-

Capital investments in biotech often aim to hit the sweet spot: early enough to warrant a discount and late enough to be sufficiently “de-risked”. Elevidys’s case demonstrates that FDA’s stance can sometimes be ambiguous, so it behooves us to make our decisions based solely on the data.

Explore the data

I created a multi-agent Retrieval Augmented Generation (RAG) app to chat with publicly accessible FDA documents, Sarepta SEC filings, press reports, publications, and abstracts related to this case. Check it out here.

References

-

Duan, D., Goemans, N., Takeda, S. I., Mercuri, E., & Aartsma-Rus, A. (2021). Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Nature reviews disease primers, 7(1), 13. ↩

-

https://www.elevidys.com/about-elevidys/what-is-elevidys ↩

-

Zubrzycka-Gaarn, E. E., Bulman, D. E., Karpati, G., Burghes, A. H., Belfall, B., Klamut, H. J., … & Worton, R. G. (1988). The Duchenne muscular dystrophy gene product is localized in sarcolemma of human skeletal muscle. Nature, 333(6172), 466-469. ↩

-

Asher, D. R., Thapa, K., Dharia, S. D., Khan, N., Potter, R. A., Rodino-Klapac, L. R., & Mendell, J. R. (2020). Clinical development on the frontier: gene therapy for duchenne muscular dystrophy. Expert opinion on biological therapy, 20(3), 263-274. ↩

-

Muntoni, F., Domingos, J., Manzur, A. Y., Mayhew, A., Guglieri, M., UK NorthStar Network, … & Ward, S. J. (2019). Categorising trajectories and individual item changes of the North Star Ambulatory Assessment in patients with Duchenne muscular dystrophy. PLoS One, 14(9), e0221097. ↩

-

Larrey, D., Delire, B., Meunier, L., Zahhaf, A., De Martin, E., & Horsmans, Y. (2024). Drug‐induced liver injury related to gene therapy: A new challenge to be managed. Liver International, 44(12), 3121-3137. ↩

-

Bhattacharyya, M., Miller, L. E., Miller, A. L., & Bhattacharyya, R. (2024). The FDA approval of delandistrogene moxeparvovec-rokl for Duchenne muscular dystrophy: a critical examination of the evidence and regulatory process. Expert Opinion on Biological Therapy, 24(9), 869-871. ↩